At the very core of medieval aesthetics lies the concept of Creation. The entire universe was firmly believed to have been designed and created by the omnipotent God, the Source of everything that is good, right and beautiful. As a natural outcome of such a worldview certain objects and systems were seen as directly modeled after the Universe itself. In modern accounts this aesthetic principle is described in terms of macrocosm and microcosm. Along with the human body and church edifices, gardens were deemed to represent the essential structure of the entire cosmos, because a garden contains within it the same harmony, rhythm and richness that characterizes the created world as a whole. In addition, a medieval garden was supposed to be read in the manner of a book, thus revealing through symbols and allegories many spiritual truths, as well as general knowledge about nature and the humanity. A trained eye of a medieval monk or an educated layman never failed to decode the message hidden in every detail of a garden design.

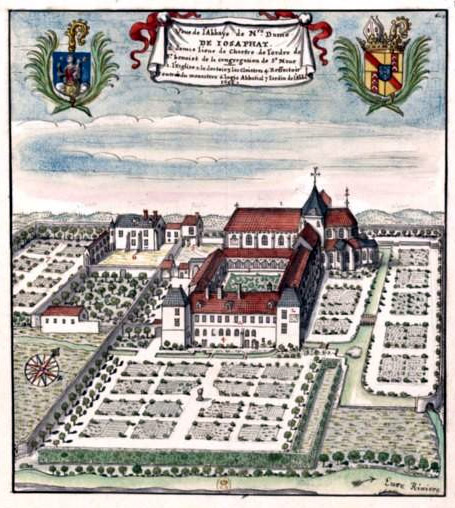

A typical monastery garden had the form of a square divided into four parts by paths. The crossing of the paths obviously pointed to the death of Jesus Christ on the cross and His subsequent resurrection. In the middle of the garden one would often find a well, a fountain or a small pond, with water acting as a symbol of life or knowledge. Sometimes, a tree planted in the middle of a medieval garden served as a reminder of Paradise. This idea helped create a new concept of an "enclosed garden" (hortus conclusus), because after the Fall the Garden of Eden became inaccessible. Also, Virgin Mary became closely associated with hortus conclusus as a symbol of perpetual virginity, chastity and yet the ability to bear fruit. The Annunciation illustration from a medieval "Book of hours" shown above has some very specific plant symbols connected with Our Lady: the white lily, emblem of her purity and holiness,the red rose, emblem of her burning love of God, the myrtle, emblem of her virginity, the violet, emblem of her humility, the columbine, emblem of the Holy Spirit, and the strawberry, emblem of the divine fruit of her womb, Jesus.

These motifs were to some extent also present in the gardens of medieval nobility, but these "enclosed gardens" of castles and estates were often more utilitarian in their use, providing herbs, vegetables and, one can assume, poisonous substances for various uses. These gardens also incorporated some aspects of "loci amoeni" (pleasurable places) of Antiquity, with emphasis of earthly pleasures.

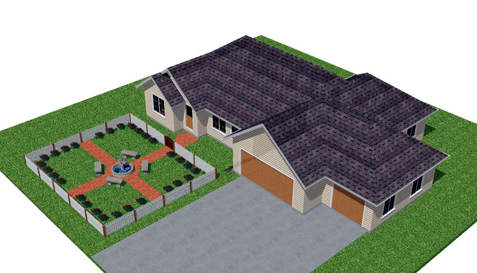

It appears that medieval notions of garden design can be easily implemented in modern times. The basic layout of such a garden would be simple, as described above, but rich symbolism must be established through the use of just a few accents. The medieval inspiration of your garden can ultimately be purely cerebral. If you have a solitary tree or a centrally located fountain all it takes is a mental exercise in seeing these objects as representations of some important universal truths and archetypes.